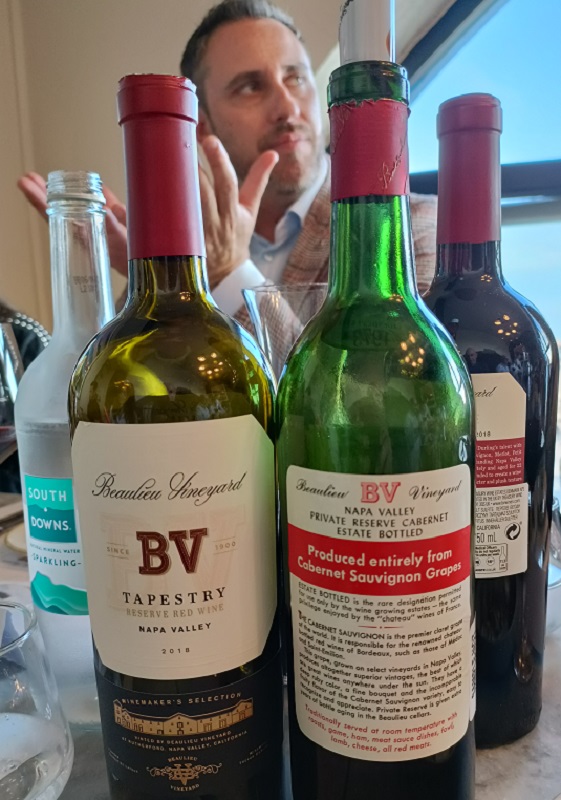

I met up with him to taste the 2018 and 2015 vintages. The 2015 is the first one he blended and marks the year Australia’s Treasury Wine Estates took over BV.

There are subtle differences in the blends, but it triggered a masterclass in extraction, barrel selection and blending Bordeaux-heritage grapes.

The 2018 Beaulieu Vineyard Tapestry Napa Valley Reserve Red Wine, to give its full name, is 78% Cabernet Sauvignon, 8% Merlot, 8% Petit Verdot, 5% Malbec and 1% Cabernet Franc. The 2015 is 75% Cabernet Sauvignon, 11% Merlot, 7% Malbec, 4% Cabernet Franc and 3% Petit Verdot. In more recent vintages, like 2021, the percentage of Cabernet Sauvignon has dropped to 50%, while the percentages of Merlot and Malbec have increased.

The name, Tapestry, hints at the intricate weaving together of these five red varieties – with each contributing another layer of complexity. The Cab provides a base of dark fruit aromas and flavours (blackberries, blueberries, black cherry compote and cassis). Merlot softens the tannin and adds plush mid-palate texture as well as some riper notes of plum, cherry and blackcurrant. Malbec brings additional dark plum and blackberry notes. Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot complete the blend with darker berry fruits, savoury spices, delicate floral and woodsy nuances.

French oak – 60% new – adds notes of mocha and caramel, heightening the aromas and lengthening the finish.

The high quality of the components is ensured by optical sorting, cold soaking, early, gentle extraction and in-barrel malolactic conversion.

Together, it allows this beautifully complex and balanced Californian wine to showcase the best of Napa Valley grapes in any given vintage.

But Tapestry is often overlooked, with BV getting more attention for its Cabernet Sauvignon varietals, Georges de Latour and Rutherford. It’s understandable: Beaulieu Vineyard is a benchmark Napa Cabernet producer and Georges de Latour, which is named after the Bordeaux businessman who bought the vineyards in the Napa Valley in 1900 (on the proceeds of selling his tartrate crystals business), was California’s first cult wine. And it is still one of America’s most sought-after and collectible wines.

But at a tasting of a selection of BV’s bottles in Brighton, in southern England, Tapestry was the wine I kept returning to over dinner. It has an open, expressive "drinkability" factor. It’s also one of the “best food-pairing wines that we produce”, according to Trevor (above).

Tapestry, whilst predominantly based on Cabernet Sauvignon from the Rutherford Bench, allows California-native Trevor to stitch a blend of Bordeaux varieties from vineyards across the length and breadth of the Napa Valley. Roughly half of the Cabernet Sauvignon was grown on the famous western benchland of the Rutherford AVA, with the balance coming from the Calistoga, Oakville and St Helena AVAs. The Merlot is from vineyards in the warmer parts of Carneros and the Rutherford Bench. The Petit Verdot and Malbec are from BV’s estate vineyards in Rutherford. The small percentage of Cabernet Franc comes from two locations, providing two styles. The Cabernet Franc from cooler Sonoma Valley provides fresh acidity and a slight herbal character; the grapes from warmer Calistoga contribute ripe and expressive red fruit notes.

“This is a wine that I love to talk about and I love to make for the main reason that there are the fewest amount of winemaking rules when it comes to Tapestry. So, you know, winemakers hate rules, right? So, this is labelled as a red blend. That means that I am not held to any specific percentage of any one varietal,” Trevor elaborates.

'I can put the best blend together from what Mother Nature has given'“I can put the best blend together from what Mother Nature has given us for that growing season. Now the one thing that each vintage of Tapestry will have in common, and it goes back to (the first vintage in) 1990, is it’s gonna be a combination of the five main Bordeaux grapes. So, it’s pretty much always going to be based on Cabernet Sauvignon. Merlot and recently Malbec are kind of the next largest contributors and then Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc to round them out. Of course, each one of those brings something unique to the table and you may have incredible variation from year to year in what that blend composition is – which I love, because it’s meant to be a story of what Mother Nature has given us, right? That being said, there is that kind of core of consistency or house style because they all come from the same vineyards and they’re made at our winery…”

He opens the BV Tapestry Reserve Red 2015 on the terrace of the Due South restaurant on Brighton seafront. He joined BV as chief winemaker at the end of 2016 and is responsible for this blend. This wine was aged for 22 months in a mixture of French, Hungarian and American oak (60% new).

“It was blended and bottled in 2017,” Trevor continues. “2015 was a relatively warm vintage in the Napa Valley. So a little bit on the riper end of the fruit spectrum, I would say, and the beauty of that is it’s very approachable, very soft, very round, but still has a really nice level of acidity. I do believe that Tapestry is one of our best food-pairing wines that we produce. Part of that comes from the fact that a lot of the Merlot that I use in this wine comes from Carneros.”

Carneros is known for its cooler daytime temperatures and growing Pinot Noir.

“But I’m one of the firm believers that Merlot does very well in Carneros, because of the soil as well as that maritime influence,” Trevor adds. “It gives you a completely different take on the varietal – a little bit more of a blue tone to the fruit, floral, high acid, all of those things. A little bit goes a long way in this blend.”

'A little bit goes a long way in this blend'All the varieties saw a little bit of oak.

“Even the Petit Verdot,” Trevor confirms. “Less so, of course, than most of the others. I tend to actually back off significantly on the Merlot, too, because of that aromatic intensity that I’m trying to highlight…

“Another point to make is that, in the last decade, we have really been dialling the needle to low, lower toast levels. Ten years ago, I was using a lot of medium-plus and even heavy-toasted barrels. The vast majority of what I do today is medium toast, French oak, because I’m really going for that structure and complexity. I do not want to dominate the fruit whatsoever with oak.”

The two Tapestries that I try have varietal levels of Cabernet Sauvignon (2018 – 78%; 2015 – 75%). But in the recently blended 2021 it’s down to 50%. “That’s because Cabernet Sauvignon did really well, I felt, in 2015, compared to a lot of the other blenders. In 2021, I’m relying more heavily on a lot of those blenders, which, I think, is one of the things that makes Tapestry stand out so much within our portfolio.”

I mention the significant dollops of Malbec. “I love that varietal and what it’s doing in Rutherford,” Trevor responds. “It sounds kind of funny to say this, but I’m telling you, on the Rutherford Bench, on certain blocks that are not Cabernet, Malbec is absolutely beautiful.”

The 2021 has seen the percentage of Malbec increase significantly while the Petit Verdot is up a little. “That’s another varietal that’s been doing really well in Rutherford,” Trevor says.

He proves the point with the latest release of the Georges de Latour Private Reserve (2019), which has an unusually high percentage of Petit Verdot – it’s a blend of 91% Cabernet Sauvignon and 9% Petit Verdot. Usually the Petit Verdot component – which is added “to further enhance the aroma and flavour profile” – is 3-4%.

'Did we miss something?'“I think the record prior to this was 5%,” Trevor comments. It’s such a relatively high percentage that Trevor admits, “I was a bit nervous when I was going to bottle. I was going, ‘Oh man, did we miss something?”

One of the reasons they added the Petit Verdot in 2019 was for its incredible colour. “It was like black. You could tattoo yourself with it. It was a crazy colour,” Trevor says.

The other reasons were its acidity, tannins, and aromatic expression – violets and blueberries “exploding out of the pot”.

“You have to be careful because it can be a very tannic varietal,” he continues. “A little bit can go a long way. But I think we were able to capture just the right extraction that year, so that it didn’t overpower the wine. It just added focus and another layer of complexity, both aromatically and on the power.”

Until the early 1990s, the wine was 100% Cabernet Sauvignon (as the label for the 1973 version shows). But after assembling the core – a barrel selection of Cabernet Sauvignon – they see how they can take it to the next level by adding small percentages of the other Bordeaux varieties. Occasionally it’s been Merlot or Malbec, but it’s Petit Verdot that “happens to work very, very well with the style”, Trevor says.

“If it’s going in the right direction, we dose a little bit more, a little bit more, a little bit more. Ah, that’s too much, let’s back up… We have never been under 91% Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Trevor reveals they put their blends together entirely blind. “It’s entirely based on sensory,” he points out. “You can have something that on paper looks like it makes a lot of sense, and it doesn’t come together properly.

“There’re a hundred different components that go into making this wine, and it’s all done by trial and error during tasting. It’s repetitive tasting, and it takes a good six months to do that. We just followed our palates and ended up with, I think, one of the great vintages of Private Reserve that I’ve experienced, and I’ve been really surprised by it.”

The Petit Verdot, if it’s used, comes from the same block each time. If they get it right in the vineyard, then Trevor’s job is to fine-tune the extraction. He’s aided by the huge investment in the winery since 2006.

“Every single tank has its own fixed pump, which means I can control the flow at any given time over a 24-hour period, so I can spread the circulations evenly over 24 hours. We have pressure transducers on the back of our tanks that will actually tell me the pressure differential between two probes and it’ll tell me at any point in time, accurate to a 10th of a percentage point, what the Brix level is in that tank.

“So, I can map out the perfect fermentation curve to align with what I want to see given the vintage conditions. That’s another thing that has really helped us dial in how the Petit performs.”

Once the Petit Verdot and other varieties reach the cellar, the aim is to get the extraction done early.

'Let them speak for themselves'“We’re going to put a lot of input in at the very beginning,” Trevor states. “Then our job is to get them down to the (225L) barrels and not screw them up, let them speak for themselves. So, we put a lot of effort into the fermentation process, getting the extraction that we want, making sure that we have that texture. And then we go down to barrels and we leave them alone. We might rack two to three times during the ageing period, but we do not get in and overmanipulate.”

The texture of the tannin is very soft and very elegant. Trevor believes this comes from the barrel fermentation. “That is one of the tools that I use in the winery to give you that sense of approachability. So when you ferment Cabernet in a barrel on the skins, it’s a huge logistical challenge because we’re literally removing the nails, popping the hoops off, removing the head, crushing 400 pounds of must into the barrel after going through the optical sorter, putting the head back on, nails back in, and putting them on these racks with wheels on them. We roll them manually, but with a drill, a few times a day, to simulate what you get in a tank, right, because you want to keep that cap submerged. Now, the reason we do that is twofold. One, early oak integration, so the heat of the fermentation is pulling out a lot of things from the barrels that you wouldn’t get at cellar temperature – tannin for one.

“Secondly, a lot of non-fermentable sugars – dextrose, pentose, things like this, that give you the perception of roundness and sweetness – helps it seem approachable, although you’re actually adding tannins at the same time. And so, 10 years from now, the baby fat is going to dissipate, and those tannins will be more exposed, but they’ve also built those longer chains and they’ve aged appropriately.”

Trevor continues: “We tried leaving the barrels vertical and punching them down. The thing with punchdowns... they’re actually fantastic, but we didn’t get enough of the impact that we were looking for, for the label. Because you have less surface area, right? And so they weren’t what I wanted. We only do 20% this way. I want high impact that then gets blended back in.

'I want high impact'“What you want is to get that pressure build-up. By keeping them enclosed, you build up the heat that you need. Because you have the opposite problem in a barrel than you do in a tank. You don’t have the thermal mass to give you that heat to where you need to cool it. You actually need to warm them up. And so, it’s like this fine line. It took us a decade to perfect it. We used to roll the barrels by hand. When I was making wine at my former winery, we were also experimenting with this and I was one of the poor guys that had to roll the barrel back and forth across the floor to a guy over there.

“I was in pretty good shape then. We graduated to these racks with wheels on them that we could spin, but we were not getting the consistency that we wanted. So, we came up with a system where we have a (handheld, battery-powered) drill that is calibrated to a specific speed that rolls the barrel at a specific speed to give you that folding effect. You go too fast, the skins go to the outside. You go too slow, they sit there (on the surface). You want it like a (tumble) dryer.

“Each vintage is different so the first four to six barrels, every vintage, I install plexiglass heads on them so I can see what’s happening inside. When I see the ideal action, we lock in the speed.”

The barrels, in a room kept at 80°F (26.7°C), are three-quarters filled with about 400lbs (181kg) of fruit for the fermentation. Once fermentation is complete, they take the heads off, siphon off the wine, press the skins, put the barrel back together, and return the wine to the same barrels on the roller racking system. The wheels have nuts on them, so someone from Trevor’s team of two assistant winemakers can pull the trigger and turn the wheel. It’s a much easier system than rolling the barrels across the floor.

“We did 400 barrels this week,” Trevor says. “During the height of fermentation, it’ll be six rotations clockwise, six rotations counterclockwise. You do that three to four times a day until I decide that’s got a lot of tannins and reduce it to three (clockwise) and three (counterclockwise). Every day, we’re tasting a representative sample from each lot.

“We dial in the drill protocol based on what we’re tasting… It’s extremely important to stay on top of where you are in your fermentation and how your extraction is going.”

As for the barrels, there has been a move towards French oak. The 2018 was aged for 22 months in French oak (60% new barrels), but the 2015 was aged for 22 months in French, Hungarian and American oak (also 60% new).

The newest release, the 2019 vintage of Tapestry, is a blend of 63% Cabernet Sauvignon, 15% Malbec, 13% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc and 4% Petit Verdot. It is aged in roughly 60% new French oak barrels for 19 months.

Tapestry is an ever-evolving blend draped in techniques that put other Bordeaux-style reds in the shade.

English

English French

French

.png)